Reshaping Academic Careers in Germany: What is in the New 2025 Proposal?

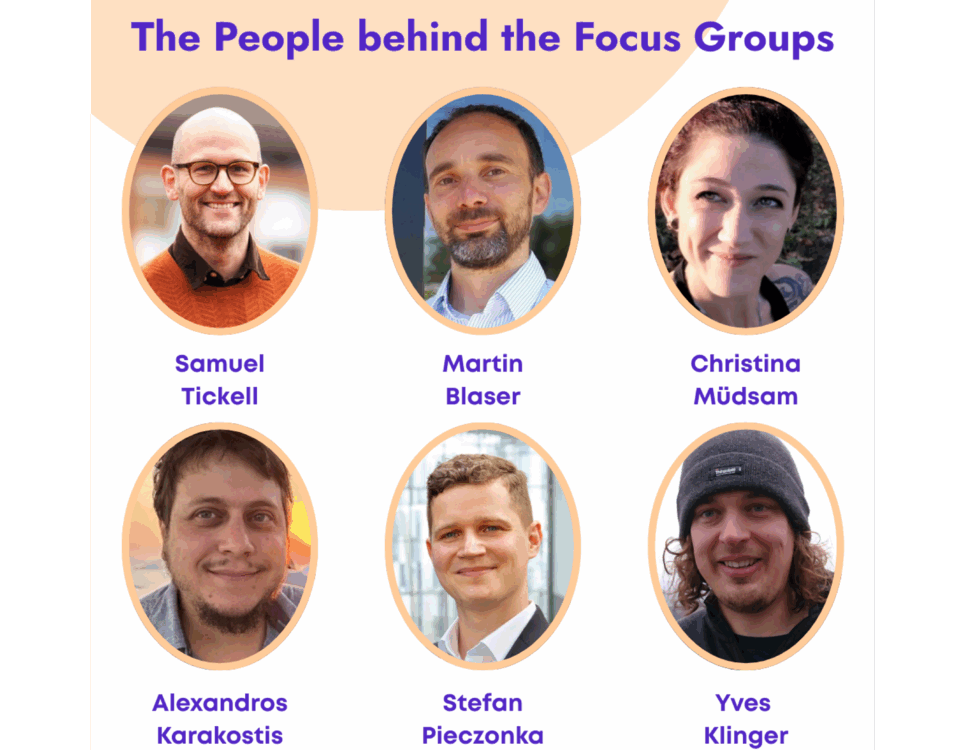

by Dr. Yves Klinger (Spokesperson WG Advocacy) and Judith Münch (Coordinator)

In July 2025, the German Council of Science and Humanities (Wissenschaftsrat) published a position paper proposing a significant overhaul of how careers in academia are structured. The goal? To make the German academic system more attractive, transparent, and internationally competitive — especially for those working in early career stages like the postdoc phase.

We have taken a closer look at what is in the paper, with a particular focus on its implications for postdocs and other researchers in the so-called “Recognised Researcher” (R2) phase of the European research career framework.

Why This Reform Now?

According to the paper, the current academic system is under growing pressure: too many fixed-term contracts, unclear career paths, and a widening gap between what academia offers and what talented researchers—both in Germany and internationally—are seeking.

At the same time, rising expectations around knowledge transfer, science communication, and interdisciplinary collaboration, along with demographic shifts (e.g., impending waves of retirements) and challenges such as AI and digital transformation, are reshaping the research landscape.

For postdocs in particular, these developments have significantly expanded the scope of responsibilities, while stable career perspectives remain scarce. The high proportion of temporary positions, the lack of clear pathways for R2 researchers, and the narrow focus on professorship as the primary career goal can discourage even those who are interested and qualified to remain in academia. The Wissenschaftsrat argues that this situation calls not for incremental adjustments, but for a fundamental reform of the academic system.

A New Career Model: S1 to S4

To address these challenges, the Council proposes a new model that defines four broad categories for academic roles, based on qualifications, autonomy, and responsibility:

- S1: Entry-level roles, typically doctoral researchers (PhD candidates).

- S2: Early postdoc positions for orientation and further development.

- S3: More advanced roles with growing independence — potentially permanent.

- S4: Professorships or comparable scientific leadership roles.

Each category can be shaped to fit different types of institutions (like universities, universities of applied sciences, or non-university research institutions), and adapted to different disciplines. The model is designed to be compatible with the European career framework (R1–R4), making transitions across countries or sectors more realistic. Within this career model, the Council argues for a clear differentiation between scientific qualification and permanent tasks such as teaching and administration.

What Changes for Postdocs?

The postdoc phase—usually seen as the most uncertain part of an academic career—gets special attention in this proposal.

In the new model:

- Postdoc roles fall under S2 (early postdoc) and S3 (established postdoc or academic expert).

- Institutions are encouraged to clearly define the purpose and duration of S2 roles. This phase should help researchers decide whether they want to stay in academia, and if so, in what kind of role.

- By the time someone moves into S3, they should be on a clear track—toward a professorship or into a permanent academic position that supports research, teaching, or science management.

The paper also emphasizes that not every academic career has to end in a professorship. S3 roles could become attractive long-term options in their own right — provided they come with permanent contracts, recognition, and career development opportunities.

More Stability Where It Makes Sense

One of the key messages of the paper is that permanent positions should become more common—not everywhere, but especially where researchers take on ongoing responsibilities for teaching, managing scientific infrastructure, or research coordination.

Currently, the vast majority of postdocs are employed on short-term contracts—even for tasks that are clearly long-term. This creates unnecessary turnover and planning difficulties, which ultimately discourages many from staying in academia. Additionally, frequent staff turnover can compromise the quality with which permanent tasks such as teaching are carried out. The proposed reform aims to change that by linking permanent employment to permanent tasks. At the same time, qualification roles, such as PhD positions or tenure-track professorships, would remain limited in time—but with better support and clearer paths forward.

More Departments, Fewer Silos

To support these new roles and career structures, the paper also recommends reorganizing how institutions work internally. One key element is the introduction or strengthening of department structures.

Instead of the traditional system where one professor leads a small team (the "Lehrstuhl"), departments would provide a more collaborative and transparent environment. This would allow for:

- More transparent and fair staffing decisions through shared leadership

- Better integration of S2 and S3 researchers and more interdisciplinary research

- Clearer division between qualification roles and long-term institutional needs

In short, departments are seen as a way to modernize academic culture and make room for diverse roles beyond the professorship.

Who Has to Make This Happen?

While the Wissenschaftsrat sets out the vision, it does not have the authority to implement these changes directly. So how is this supposed to work?

The paper makes clear that every institution will need to develop its own personnel structure strategy, based on the new model. But this will not happen in isolation. The proposal calls for coordination between universities, universities of applied sciences and research institutions, state governments, and the federal government.

To enable the reform, legal changes may be necessary—especially around higher education laws, public service rules, and teaching capacity regulations. Some federal states are already moving in this direction, for example by introducing quotas for permanent positions or revising employment laws.

The idea is to make the system more flexible and future-proof—while still allowing institutions to tailor solutions to their own profiles. Extra funding is not assumed as a requirement, but some short-term support might be needed during the transition.

What is the Takeaway for Postdocs?

The paper sends a clear signal: academic careers in Germany need better structure, more transparency, and fewer dead ends. Especially for postdocs, the idea of an early orientation phase (S2) followed by either a professorial track or a long-term academic role (S3) could bring welcome clarity. But concerns remain: Is two to three years in S2 really enough time to build a competitive academic profile? And how many S3 positions will actually be created—especially permanent ones? It is obvious that the transition while take several years, even if carried out resolutely.

A Clear Vision—But Will It Stick?

The reform proposal lays out a thoughtful framework, but much depends on what happens next. While the Wissenschaftsrat offers general guidance, it is now up to research institutions, federal lawmakers and—crucially—the 16 federal states which hold primary responsibility for research and education to act. Legal changes, especially to the Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz (WissZeitVG), will be key, but so far, they are only hinted at. Earlier proposals—including those from the Wissenschaftsrat itself—were similarly ambitious, but often fizzled out in practice, watered down by institutional inertia or legal loopholes. There is a real risk that new job categories may just give existing practices a new label, without solving the underlying problems. Further, while creating more permanent positions is a central appeal by the statement, how universities will finance them without additional funding remains an open question. Without binding rules and real incentives, there is a risk that existing problems will simply continue under new labels. Whether this reform leads to lasting change, or becomes another missed opportunity will depend on how seriously the system takes its own diagnosis.

Here you can find the full position paper from the Wissenschaftsrat and a short summary (both in German).

You can also watch a video of the press conference after the publication of the position paper.

A short summary in English is announced to be published soon.